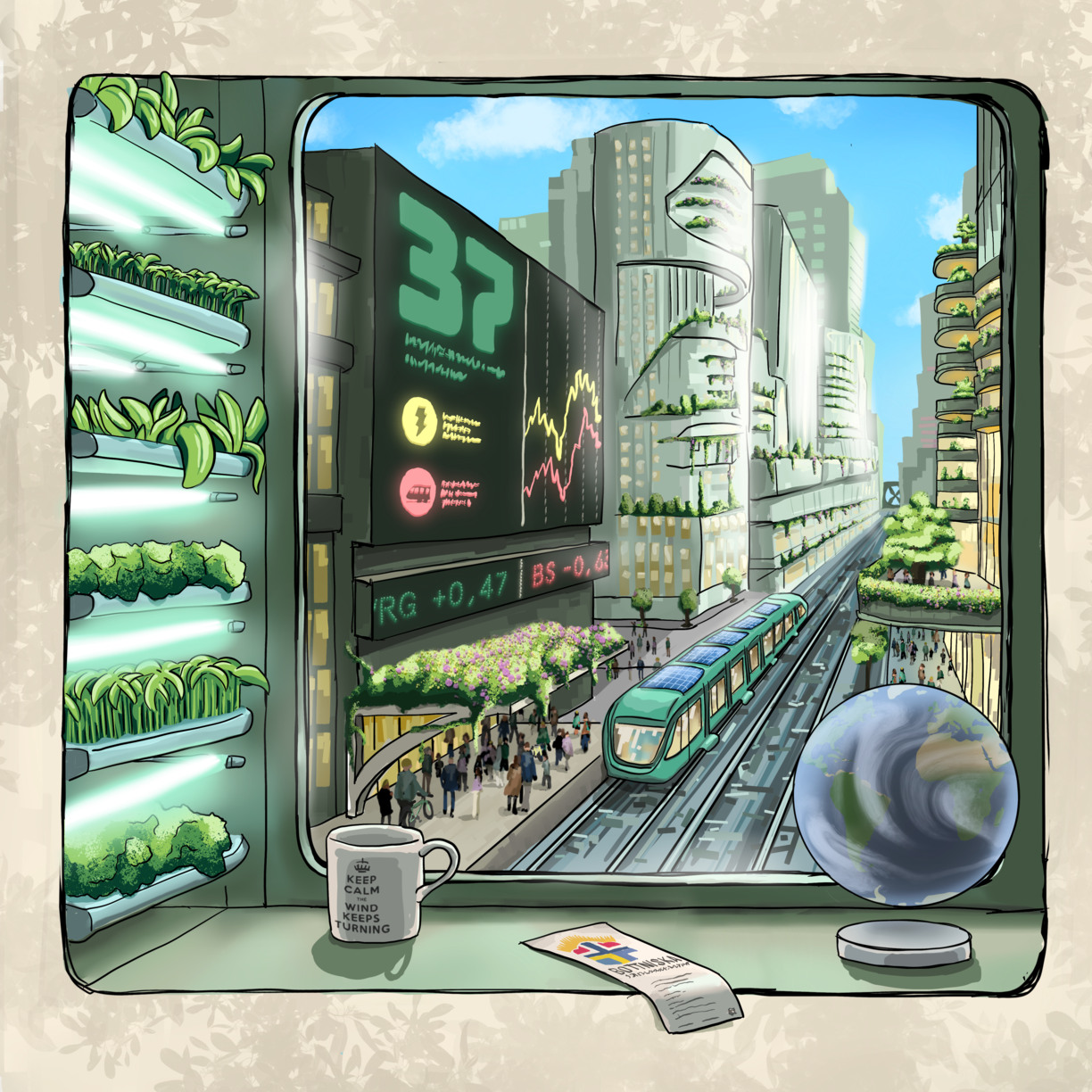

Illustration: Daniel Bjerneholt - Haus Society AB

Windy City

What do you do when there is an electricity surplus and the electricity is almost free?

How can buildings be designed to lower the energy demand during high demand periods

Read the story about Wilda, a manager at a vertical greenhouse in Windy City, who thinks she has found a way to make quick money from the fluctuating electricity prices.

Windy City

By Andrew Dana Hudson

The best part of Wilda’s job was the view. She had a corner office, tucked into the aerodynamic edge of a timber skyscraper. To the east she could see the waters of the Bottenviken, pleasurecraft lazing and swift ferries shuttling to and from the Finnish coast. To the north stood four giants: massive wind turbines, each hundreds of meters tall, nacelles level with Wilda’s window. Their three blade arms swooped around and around, nearly touching, producing, when conditions were right, a resonant hum she could almost hear. Wilda was a recent transplant to the Skellefteå-Luleå Urban Energy Corridor a.k.a. Skelluleå—the narrow stretch of rail-connected power parks, factories, and dense mixed-use developments that almost constituted a single hundred-kilometer-long city on the Bothnian coast. Other newcomers sometimes complained about the noise, but to her it sounded like opportunity.

Wilda spent a great deal of time looking out her windows—north, more than east—because her job kept her at her desk most of the day. At Höga Tornet Grönsaker AB, the agricultural coop she worked for, a ‘Farm Manager’ was more manager than farmer, it turned out. Professionally, it was a plum position, which was why she’d moved with her young son up from sweaty southern Sweden to take it—that and a desire for a fresh start after fleeing a relationship that had spun violently out of her control. The distance from the stomping grounds of her ex was good, but she found herself missing the rest of her support system. Personally, emotionally, she was wondering each day if she’d made a terrible mistake.

It wasn’t getting her hands dirty that Wilda missed, though there was that. It was the weather. There was just no weather inside the vast, gurgling hydroponic farm she now oversaw. The vertical garden occupied an impressive ten storeys of the wooden tower, snugged between the rooftop restaurant (which served VS’s greens and kale) and the bloc of social housing that extended down to the ground-level retail. A worthy amount of acreage, and denser than all but the most labor-intensive permaculture plots. But all of it was inside and climate controlled—heated and cooled and pumped and illuminated by the plentiful power generated by Skelluleå’s patchwork wind parks.

This was a big change from down south, where farming had meant keeping a wary eye on the horizon. Sweden had met its decarbonization targets in a big way, but not everyone else had, and the world was in for a few long rounds of baked-in climate chaos while the UN argued about a carbon removal treaty. One never knew what the greenhouse-juiced atmosphere might pull; the bondepraktika of her ancestors was obsolete, and the weather reports unreliable, so all that was left was rugged vigilance. More than once during her teenage years working the land, strange summer hail and ferocious winds had blown in, and Wilda had been the first of her family to run out and drag tarps over their fields to keep the crops from getting bruised and blown away. She prided herself on her weather eye, but here in the north, with its bleeding edge everything and its timber hyperurbanity, her eyes were mostly used to look at spreadsheets.

It took Wilda six months to notice that there was actually a connection between the weather out her window and the farm management metrics on her monitor. It was the power prices. When the wind was blowing—and she could see it blowing, because she could see the spinning of the four great turbines—electrons soon got cheaper. The VS facility used a lot of electrons. Not as many as the heavy industry the Skelluleå corridor had been built to power—the battery factories and carbon-free steel plants, the green fertilizer and the graphite, and more—but enough that a price shift of a few öres, or more than a few öres as often was the case, made a real difference to the coop’s bottom line.

So Wilda started keeping her weather eye on the turbines, and her other eye on her monitor. It was fun, even exciting, to watch the wind pick up, and then, a few minutes or even seconds later, see the immediate cost of a kilowatt-hour dip. Norrbotten, with its big buildout of wind power over the transition decades, had cheap but volatile energy prices, in part because ties to the south—infrastructural and increasingly cultural—were throttled by development gridlock. When the wind really picked up, and the sun was bright, and demand was down, one could even get paid to take electrons. Some people opted for locked-in annual rates, to avoid having to worry about price spikes. But that meant missing out on those golden, gusty days.

The farm, being a delicate operation, had its own sizable battery, and Wilda, with a little digging, got a handle on the algorithm that interfaced with the grid. The default settings were quite conservative, almost price agnostic, optimized for battery health instead of rates. Wilda nixed them and put a dashboard up on her screen.

At first she just bought low, snagging a few kilowatt hours to top off the farm’s battery whenever the price dipped. Pretty soon, she figured out she could also sell high, tapping the battery to give power back to the grid for credit. Not long after that, browsing energy management tips online, she discovered that she could even trade in electron futures and shorts. It was at that point that Wilda fell way down the rabbit hole.

Maybe it was being stuck inside all day, questioning what exactly she was supposed to be doing with her life. Maybe it was being so far from her friends and family in the south, only able to visit via an aging, achingly slow rail line or a shameful, carbon-taxed plane flight. Maybe it was her son, who didn’t understand why they had left the home he’d been used to. Maybe it was the north’s endless midsummer light messing with her sense of time. Maybe it was just in her nature; she had played a lot of crown-hand poker at gymnasium. Whatever the reason, that first summer in Skelluleå, Wilda got super, super into the arcane, financialized world of electron trading.

From her desk, benignly neglecting her crops, she could gaze out the window and make tiny money moves based on the thrum she felt from the turbines or the clouds rolling in to shade the city’s PV rooftops. It was like a gamified, slightly addictive version of watching the horizon on her family farm down south, only faster and with smaller stakes, a crown here, a few euro-cents there. But those crowns added up.

More than the money, though, what Wilda liked was feeling connected to the energy system and to the shifting, mercurial natural forces that mostly powered it. She even got a pair of birder binoculars and used them to peer at the maintenance workers in their harnesses, scurrying carefully around the turbines’ nacelles. She wondered what it would be like to be out there, harvesting energy straight out of the sky.

#

The worst part of Sneha’s job was the view. It wasn’t that she had a problem with heights; you couldn’t work on 300 meter tall turbines and not be comfortable with a little wind in your hair. No, the problem was that the view was too good, so good that tourists were clambering to get on top of the corridor's biggest wind turbines.

Every summer Sneha, a tour guide with the Skelluleåkraft utility, was put in charge of unruly packs of overdressed Germans and Italians, all of whom now seemed determined to fling themselves from the edge of the turbine blades. Tourism was a big business in Skelluleå, as more and more Europeans—and Indians, and Arabs, and Africans—traveled north for the summer to escape the worsening heat. When they arrived in Norrbotten, of course they wanted to see more of the huge structures that dominated the urban landscape. And the utility, keen to get the most out of their massive investments in the turbines, was happy to show them.

Sneha would herd the tourists into the cramped lifts and take them up, four at a time, to the interior of the nacelle. She’d painstakingly explain the gearbox, the generator, the braking system, the control package. Then, if the wind was low enough, she’d hand out harnesses, clip them onto safety lines, triple check everything, and take them up top to the fenced-in little viewing platform, where they would get a wide, wild view of the other turbines, the timber skyscrapers, the ragged Skelluleå coast. If the air was still enough, and the breaks were on for maintenance, and they got the permits, she’d even supervise daring walks out onto the long, ever-so-wobbly wingblade, to film yoga stunts or viral dances.

For years before the incident, Sneha had relished her job as a tour guide. She had never been overflowing with charisma; she’d alway felt a bit in limbo, caught between three very different cultures. But she was also good at languages, which helped, and she was a quick study when it came to the intricacies of wind power and the sophisticated mechanical engineering inside the turbines. She’d grown up around the wind parks, which her parents had helped build. The gig paid well, and she got occasional tips from richer foreigners who liked to sling their money around.

Then one golden, gusty day the summer past, Sneha was just finishing up her spiel—explaining that unfortunately the wind was too strong for outdoor viewing—when a French guy in wraparound sunglasses and a bulky coat had suddenly bolted up the short ladder, popped the hatch, and hauled himself, unharnessed, onto the top of the nacelle. In the tight, crowded space, Sneha couldn’t move fast enough to stop him. By the time she’d clipped into her own harness and poked her head out, the guy was long gone.

Apparently the Frenchman had been a famous base jumper, notorious for making unpermitted leaps off tall structures. On this particular jump, however, the wind was perhaps stronger than the daredevil had been anticipating, channeled toward the turbines by the aerodynamic forms of the corridor’s shapely timber skyscrapers. The jumper was blown head over heels, his parachute tangling, and he landed heavily in the busy park below the turbines. Amazingly the Frenchman survived the fall with only a sprained ankle.

The incident left Sneha shaken and disillusioned with her job. She found herself torn. On the one hand, she was increasingly anxious about interacting with tourists, even with the new safety regulations put in place after that day. In her paranoid imagination, every person she led up the lift was now a potential jumper. On the other hand, the pay was nice, even essential. Sneha had many mouths to feed.

Sneha was the reluctant matriarch of a small and growing clan: her own three children, plus her three sisters and their children, plus assorted hangers-on. A generation earlier, her mom and dad had moved to Norrbotten from Gujarat and Shenzhen, respectively, to help meet the shock demand for labor in the booming north. They met in a barracks kitchen, before urban development of the Skelluleå corridor got fully underway, when workers lived packed into rudimentary temporary housing. There they had, by all accounts, a torrid romance, followed by marriage and four kids.

Several decades later they retired back to India, declaring that they couldn’t take another snowy, dark winter. Sneha, the eldest, who’d been born in Skelluleå and had no problems with snow and darkness, was left in charge. Being in charge, it turned out, meant paying for things, like family vacations and ski passes and fashionable clothes for the teenagers.

Sometimes Sneha looked out at the world from atop the turbines, taking in the timber skyscrapers that clustered in a narrow checkerboard pattern around the wind farms. She thought surely somewhere, in that big city of hers, the second biggest in Sweden, there was an easier way to make a living.

#

They met, as parents often do, picking up their kids up at the train station. Small talk at first, as the trains arrived in quick succession, kids spilling out, detaching from their little knots of kid-drama, chaperones waving them off or chasing them down with forgotten hats and bags. Wilda and Sneha found themselves the last mothers waiting, each checking their phones to confirm that the next train was the cheapest, and they realized they had something in common.

Wilda and Sneha were both minute-raters. Like many services dependent on the grid, the electrified light rail tickets varied based on the ever-changing supply of energy, tugged up and down by the rising and setting of the sun, the changing of seasons, the weekly shifts in wind patterns—and by demand, the uneven rhythms of human need and activity, individual and collective and institutional. Sometimes electrons were scarce, and sometimes they were plentiful. Never too scarce, thankfully, not with big batteries and hydropower plants in the mix. Nor too plentiful, not with hydrogen electrolysis to run to keep the steel plants fed, and the occasional DAC facility springing up, and stopstart computation projects crunching weird numbers, all of which could run hard when power was cheap and go still when it wasn’t. But nonetheless, the variability was real, and human behavior could do much to soften the edges, if people got the signal which way the wind was blowing, so to speak. What was price if not the clearest, most irresistible signal ever invented?

For some these fluctuations in energy cost were a mild annoyance, one obviated by transit passes and rate-lock energy plans and investments in home batteries managed by algorithms. But plenty of others, like Wilda and Sneha, decided they could surf the waves, either to save money, or do their civic duty helping optimize the grid, or just for the fun and challenge of it. Ratepayers could opt to get their price signals by the week, by the day, by the hour, or even by the minute.

Which was why Wilda had instructed her son, and Sneha her three daughters, to wait the extra twenty minutes to take the train that could catch the trough of the afternoon’s price dip. By the time their kids arrived, they were already laughing about it together, in that relieved, conspiratorial way people always laughed when recognizing a kindred spirit. And so they did what anyone would do: they decided to grab a fika.

“You work on them?” Wilda said, when they met up the following week. “Like on top of them?”

The them was of course the turbines. They sat in the intermittent shade of one, at the outdoor seating of a cafe that served Swedish-style sandwiches, Indian-style sweets, and Turkish-style coffee—such were the tides of globalization. Down at street level, protected by the breaking effect of close-planted and wire-anchored trees, the wind that rushed through the turbines was not more than a firm breeze. The hum was noticeable, but not so much more than the rattle of the elevated trains above and the artificial chirps of electric cars gliding cautiously through the lunchtime pedestrian traffic.

Sneha, used to commanding a rabble, had no problem talking over that base layer of white noise, and she was pleased that Wilda met her volume. Wilda had that easy confidence that Sneha associated with certain Swedes from the south. She found herself drawn in by the other woman’s intense and undivided attention.

“Sometimes, though inside them more than on top,” Sneha replied.

“I’ve been meaning to go on a tour ever since I moved here. Any chance you could give me one?”

Sneha suppressed a wince, but agreed.

#

So a few days later Wilda joined Sneha on one of her tours. Along with a small clump of tourists, they ascended the lift and talked through the different considerations that had led turbines to get so big and then top out at their current height: the increased windspeed higher in the air, the translation of that speed into torque to prevent the blades from flying apart, the stressors put on the tower, the base, the internal gears. Sneha was relieved that her new friend showed no desire to fling herself from a great height, and indeed seemed genuinely interested in these technical details. For forty minutes, Sneha felt back in her groove, even cracked a few wind-based jokes.

For Wilda, the tour was a revelation. She’d spent so much time thinking about the abstractions of energy prices, she’d almost forgotten that those prices reflected very material concerns. And not just the weather, but what was going on inside the turbines. She started to get an idea. The question was: how to bring it up to Sneha.

“Ever looked at the electron markets?” Wilda asked, next time they got together, watching her son clamber on a playground rope structure with Sneha’s youngest. “You’re in the sector, after all, and you minute-rate.”

“Not really. Minute-rating is just part of the work culture at Skelulleåkraft, even in the maintenance department. I suppose it’s a way to make sure everyone is paying attention to the larger trends. Though with a big family like mine, hitting the lowest prices makes a big difference.” Sneha felt a twinge of unease. The fast-paced financialization of the energy system had always seemed to her a bit out of touch with the realities of delivering electrons and keeping prices low for all. “Why? Are you a trader?”

“I dabble,” Wilda said, an understatement. “The tour just got me wondering. I know how much wind variability impacts prices—I can see it out my office window—but how much comes from what goes on inside the turbines?”

“All of it?”

“I mean maintenance and repairs. When they put the brakes on to go out on the blades. When they disconnect the generator. That sort of thing.”

Sneha shrugged. “But that’s only one turbine at a time. There are dozens in the corridor. And they spread out the work as evenly as possible. It can’t make too much of a difference in the prices.”

“Ah, yes, of course,” Wilda said. Then, innocently, “Do they give you the real maintenance schedules?”

The weekly maintenance schedules were made public, so all trading on the market had the same information, but as with everything the reality tended to be different when the actual day arrived.

Now Sneha was no fool. She’d survived raising three toddlers, each one briefly more sociopathic and megalomaniacal than the last. She knew when someone was trying to put something past her and get something out of her at the same time.

“Why?” she asked, eyes narrow.

“I was thinking…” Wilda chose her words, “prices are so sensitive these days, if there was a master spreadsheet of planned maintenance, maybe there’s something on there. Some day with more downtime than usual. Something that might be very interesting to a smart energy trader. Profitable even.”

“I’m sure I don’t know what you mean,” Sneha said, and she got up to go wrangle her children.

#

It might have ended there—an amateur attempt at insider trading spoiling a budding friendship—if not for the Bothnians.

The Bottniska Självständighetspartiet was an extremely motley regional separatist movement that nonetheless was gaining prominence in Norrbotten. Inspired by a mixed bag of historical and contemporary grievances against Stockholm—exploitation, underinvestment, overdevelopment, lack of autonomy, neglect—the Bothnians wanted to throw off southern rule and instead form a new latitudinal alliance of everyone north of the 63rd parallel, on both sides of the Bay of Bothnia.

Critics were quick to point out that the Bothnians didn’t have a definitive party line. Were they autonomists? Secessionists? Expansionists? Somehow all three at once? The movement was open source and meme-driven, a throwback to the chaotic politics of the teens and twenties, a reversion to complicated populism after decades of the firm, knuckled-down technocracy that had gotten most of Europe through the energy transition.

Unlike the Catalans, the Scots, or the Sicilians, however, the Bothnians didn’t just want independence from Southern Sweden and rule by Stockholm. They also wanted cross-border unification with the other Scandinavian frontiers: Västerbotten, Norrbotten, Finnish and Swedish Lapland, Norwegian Nordland and Finnmark, and even Murmansk Oblast, which was turning its eyes west after Russia’s extended disintegration. The Sami indigenous peoples had already spent decades resisting the imposition of arbitrary borders dividing up the land their reindeer herds had roamed for centuries, and the Bothnians took up their cause and (perhaps inappropriately) claimed it as their own. It was closer to Cascadian Separatism than anything, a bioregionalist movement seeking to form a new-old unit of autonomy based not on language or history but on climatic and infrastructural common interest.

Just what that common interest entailed, however, was quite up for debate. For some, the #FreeBothnia trend was an excuse to agitate against immigrants and those of non-Scandinavian descent. For others, it was the opposite, a platform to demand less stringent migration policies and to embrace the Northern multiculturalism that had, starting in the boom years, outpaced that of the South. For some it meant true indigenous sovereignty, and for others it meant getting the north out from under the Sami agreements that were holding back its development.

But a big part of the kerfuffle was about energy. Norrland had a lot of it, and the south—facing a price squeeze from Europe thanks to the Flamanville disaster and the subsequent shutdown of France’s nuclear fleet—now wanted it. Plans were under consideration in the Riksdag for a major expansion of high voltage power lines to bring abundant Norrbotten electrons down to hungry Stockholm.

Way the Bothnians figured, they’d built the huge wind parks and the next gen hydroelectric plants, not to mention the green steel used in the construction. Why should Stockholm suddenly get to claim the fruits of their labor—especially when (and this was a popular grumble) the same politicians now calling for an emergency transmission blitz had spent years blocking a high speed rail connection between Skelluleå and the south? Why countenance a fresh round of extraction, when they could instead join forces and cultures with their comrades across the water, who had worked with them to pull the continent—indeed, the world—out of the climate death spiral? Didn’t the more robust grid connections laterally to Norway and Finland mean something? A shared destiny perhaps?

Such was the rhetoric coming out of the mouths and into the cameras of the four Bothnian activists that emerged from Sneha’s tour group, two weeks after that day with Wilda at the playground.

These folks were daring but not daredevils; they waited until she’d clipped them in, picked a tour when the brakes were on and the winds were calm. Once on top, however, they suddenly turned their phones on themselves and began shouting demands into what was obviously a live broadcast. They produced spools of fishing line, tossed them down to collaborators waiting in the park below, and used high-powered autoreels to quickly haul up a lightweight but nevertheless very large banner, which they clipped to the top of the nacelle. Then, ignoring Sneha’s protests, two of the Bothnians carefully made their way out onto the long blade of the turbine. There they secured themselves with a suction-apparatus, and refused to move.

The ensuing ordeal lasted six hours, which Sneha spent on the phone with both the police and her bosses at Skelluleåkraft, trying to talk the activists into returning to safety, feeling surreally part-hostage and part-hostage negotiator. Along with a spectacle that could be seen for kilometers around, the Bothnians, by simultaneously occupying this and six other turbines, succeeded in making energy prices marginally spike across the corridor, such that even day-raters might get an alert notification, depending on their settings. This, they claimed, was but a taste of the pain ratepayers would endure if Stockholm got its way.

For Sneha, this was the last straw. She felt sure this sort of thing would keep happening as long as she worked in the turbines. Her employer was understanding, offering to move her to an admin position with some emotional distress compensation. But Sneha didn’t want to work a desk job, and that compensation was not as much as she felt like she deserved. She decided she would be turning in her notice—just as soon as she’d heard a bit more about Wilda’s idea…

#

“Oh wow!” Wilda said, when she heard the story. She’d seen one of the banner drops from her office window, but she’d had no idea her recent acquaintance had been up there. “So you’ve decided to do an Office Space?”

Wilda had not expected to hear from Sneha again, and for her part Sneha had planned to do no more than nod to Wilda across the pick up line. But here they were, sitting and sweating together in a floating sauna, tethered in one of the many half-developed islands along the Skelluleå achipelago. It was the best place Sneha—not exactly an op-sec expert—could think of to have what felt like a somewhat illicit conversation.

“Something like that,” Sneha said. “How does it work?”

So Wilda talked about short selling and put options, those financial sleight-of-hand tricks that had long ago turned every kind of market into an arena for gambling. She walked through how the summertime easing of Höga Tornet’s heating and lighting costs gave her a significant amount of storage to play with using the farm’s battery—not enough to make real money, but enough to bet bigger than a semla.

Then, getting up to pour water onto the sauna’s scalding rocks, such that they let out an angry hiss, Wilda whispered about the autotrading tools she’s found in the Deep Web. Outside of hand-curated media feeds and population-limited, human-moderated forums—the guarded cyberspace pastures most people wisely never strayed from—there existed a churn of bots, jailbroken generative A.I.s all talking and coding unintelligibly and unintelligently to each other. No one particularly wanted the Deep Web there, but at this point the bots had wormed their way into the foundations of the world’s digital and financial infrastructure, and there was no way to root them out without also exposing the pools of dark money that kept the world’s powerful rich and the world’s rich powerful.

So daring digital spelunkers could delve into this cacophony and return with strange artifacts: protocols for creating hundreds of Caribbean shell companies at the touch of a button, botnets for brute forcing through financial spam filters, high-frequency self-selling swarms for pricepumping novel coinstacks, creative agents that could be tasked with pursuing certain goals with a relentless, instinctual yearning. These novel tools would only work once before the world’s digital-financial-legal immune system got their number, but with a little bit of real-world leverage—say, insider info that could help predict a small energy price flux well in advance—they could (probably) make for one spectacular day on the markets.

Wilda was a farmer, not a hacker; she didn’t have the technical know-how to pull off such a katabasis. But she was a quick learner, and she’d followed hints and links down to the discussion boards that existed, metaphorically, at the very edge of the Deep Forums where people traded in such semi-illicit weirdness. She had, she was pretty sure, a plan.

#

“Well, my plan didn’t work,” Wilda reported a week later.

They were fishing this time, or rather their kids were, all gleefully flinging bobs into the stream and pulling them out again so fast no fish would be able to bite even if one wanted to. On the far bank a Bothnian march was parading through town, their signs an aggressive but confusing jumble.

“What happened?” Sneha scowled at the Bothnians and batted away a mosquito. “I got you the schedules. Did your friends not help?”

Wilda had gone to a clique of Deep Web enthusiasts she had wormed her way into, bearing Sneha’s spreadsheet like an offering to a choosey god. They had been charmed by her cheek and so coaxed the appropriate tool out of the unthinking roil of computation, but they had handed it over with bad news.

“They did, but turns out the schedule is not enough,” Wilda sighed. “You were right. Skelluleåkraft spreads out the maintenance too much to impact the prices. Maybe there’s an infintesimal shift, but it’s drowned out by weather noise. We have the means, we just don’t have a window.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning without a way to predict a price change—a bigger one than the tiny fractions of a percent the maintenance schedules induce—this whole thing is cooked.”

“And we can’t use this when the weather changes?”

“Not unless we can predict the weather better than anyone else, and I don’t think we’ve got the algos for that. The point is to get ahead of the rest of the market. It has to be something human.”

Wilda glumly watched at her son, fishing as fast as he could and catching nothing. Sneha watched the Bothnians, feeling frustrated—and then, much to her surprise, she started with eurekic revelation.

“I think I know just the humans who can make that happen,” she said.

#

Wilda and Sneha were surprised at how easy it was to get into the Bothnian general assembly. But that was the thing about these ‘open source movements’ that often proved so sticky and troublesome: they were open. The whole point was to make it easy to join up.

So after the parade had passed, Sneha went across the stream and found a dropped paper flyer. That led them to a meeting, packed into the community room of Skelluleå’s largest kulturens hus. There it was only a matter of standing around listening to speeches, trying to pick up the weird hand-signal language that attendees used to express their enthusiasm or disapproval of various proposals and plans of action—a revived relic of early-century anarchist spaces that had recently become trendy in various anti-establishment movements.

“They talk about southerners like we’re all blood-sucking vampires,” Wilda complained in a whisper. “I didn’t have anything to do with the stuff they’re talking about.”

“You did come up here and take a northerner’s job, didn’t you?” Sneha chided. “Anyway, I’m sure half these people would take a southerner over someone with my background.”

“Yeah, what do you think the plan is for that? Are they just going to live with racists in their ranks?”

“It’s either split up or suck it up, I guess. What else can you do about contradictions?” Such was politics in messy modernity.

Eventually breakout groups were called, and Wilda and Sneha surreptitiously shuffled over to where hands were waving for those interested in “future direct actions.”

“We were so impressed by the turbine banner drop,” Wilda gushed to the group a few minutes later. Next to her Sneha tried not to look like she was fuming. “It really got us thinking. Is anyone planning anything like that again? The wind parks are such a…a symbol of everything good about Bothnia that Stockholm is trying to take away.”

Others in their breakout group nodded excitedly. The banner drop had indeed been a big hit.

“You never know,” Stefan, the bushy-chopped young man leading their group, said slyly. “But it sounds like you get it. Give me your contact info, and we might let you know.”

#

This was not the result they had hoped for, but they didn’t want to push it. So after the assembly—which did, despite their misgivings and despite their intentions, leave the two women just a bit more sympathetic, on the whole, to the Bothnian cause—Wilda and Sneha went home and waited.

To their surprise, a few days later the Bothnians reached out. They had both passed the group’s cursory background check by virtue of being actual people and not undercover cops. Apparently Wilda had demonstrated the right kind of “zeal of the converted,” such that they would overlook her own southern origins. And Sneha’s job at Skelluleåkraft was exciting to the group. That would make the whole operation easier!

“Are we in over our heads?” Wilda asked Sneha in the train station.

“This was your idea!” Sneha hissed.

“Not this part. This part was your idea.”

Despite this bickering, however, both felt an urge to go through with this caper that they didn’t quite understand. They were a bit like giddy, wild teenagers, riding around at 1AM, doing wheelies and blaring music and shouting their laughs into the nonexistent night. Soon enough the seasons would turn, and everyone would be in for a long, dark, snowed-in winter. They wanted to make some trouble while they had the chance.

So they said yes to the Bothnians. “We’ve been studying the tactics that movements used to force petrostates to abandon fossil infrastructure,” Stefan, their cell leader, enthused. “This action will be even bigger than the last one!” Which meant bringing even more turbines to a temporary standstill, a bigger (if still brief) shock to the energy system. Which all suited Wilda’s gambling tool just fine.

The plan was set but the date remained in flux, waiting for the weather conditions to be right: a calm morning during which maintenance could proceed, with winds expected to pick up in the afternoon. Sneha was going to be tour guide again, taking a small cohort—including Wilda—up to the top. And she gave up vital information: instructions on how to engage the brakes on the turbines and avoid the various safeguards that had been put in place since the last banner drop, so other teams could reliably execute their disruption.

The day of the action arrived before they knew it, before doubts and second thoughts had time to cohere. They got word first thing in the morning. Wilda rushed to set up her shorting tool. Sneha went to work, suddenly, silently freaking out, but also not feeling like she could back out. Here she was, about to help—even represent—a political cause she didn’t exactly agree with and didn’t even really like, that had sightly traumatized her during their last stunt. Why? At this point she couldn’t quite say, other than that she didn’t want to let Wilda down.

#

“We’ve got a problem,” Stefan said on the ride up to the nacelle, handing them balaclavas. “We were supposed to be two more, but they didn’t show. I can run the camera alone, but you two will need to take their place.”

“Take their place doing what?” Wilda asked, nervous.

“Going out on the blade.”

This was not what the pair had bargained for, but events barrelled along. In no time they were out on top of the turbine, the banner deployed, the barest light breeze touching their faces. The city stretched out before them, nonetheless buzzing with activity and energy.

“Oh, this was a bad idea,” Sneha said, looking out at the eye-wateringly long turbine blade, painted a flashy black to warn off the birds.

“Yeah,” Wilda agreed, “but now we’ve got money riding on it.”

Though their faces were covered, they still felt exposed as Stefan’s camera setup came on and began to broadcast, via Stefan’s commentary, various Bothnian grievances.

“I don’t think I can do it,” Sneha said. The wind was picking up now. She’d never been bothered by the heights, but now she couldn’t stop thinking of the base jumper flinging himself off into a near-deadly tumble.

“We’ll go together,” Wilda said, and took her friend’s hand.

#

By the end of the day they had both been arrested, charged and released, and Sneha had been fired, which she was mostly fine with. The Bothnians had a solid legal team that would help them, and the pair agreed. At this point looking like less than zealous supporters of the movement seemed like a good way to get their true motives discovered, and—given how it had turned out—that would be bad.

Because sitting buried in a hashed crypto wallet, freshly laundered by Wilda’s Deep Web shorting tool, was quite a tidy sum. Was it a life changing amount? They’d see. But it was way more than the small-time trades Wilda had done before. Perhaps the biggest total payout a retail trader had ever made in the energy markets. Maybe soon the forensic accountancy algorithms that patrolled the markets would spot their maneuver and take it all back, but for now it was theirs.

Wilda and Sneha took the train home from the police station together. They watched the minute-rate prices on their phones, letting a few more expensive lines pass while they waited for the winds to pick up, and electrons to flood the grid, and inch the rates down a few points. Everyone, it seemed to Wilda, followed the price signals in one way or another. All they’d done was create one of their own.

Updated: